Spain Tightens Restrictions on International Surrogacy: What It Means for Intended Parents

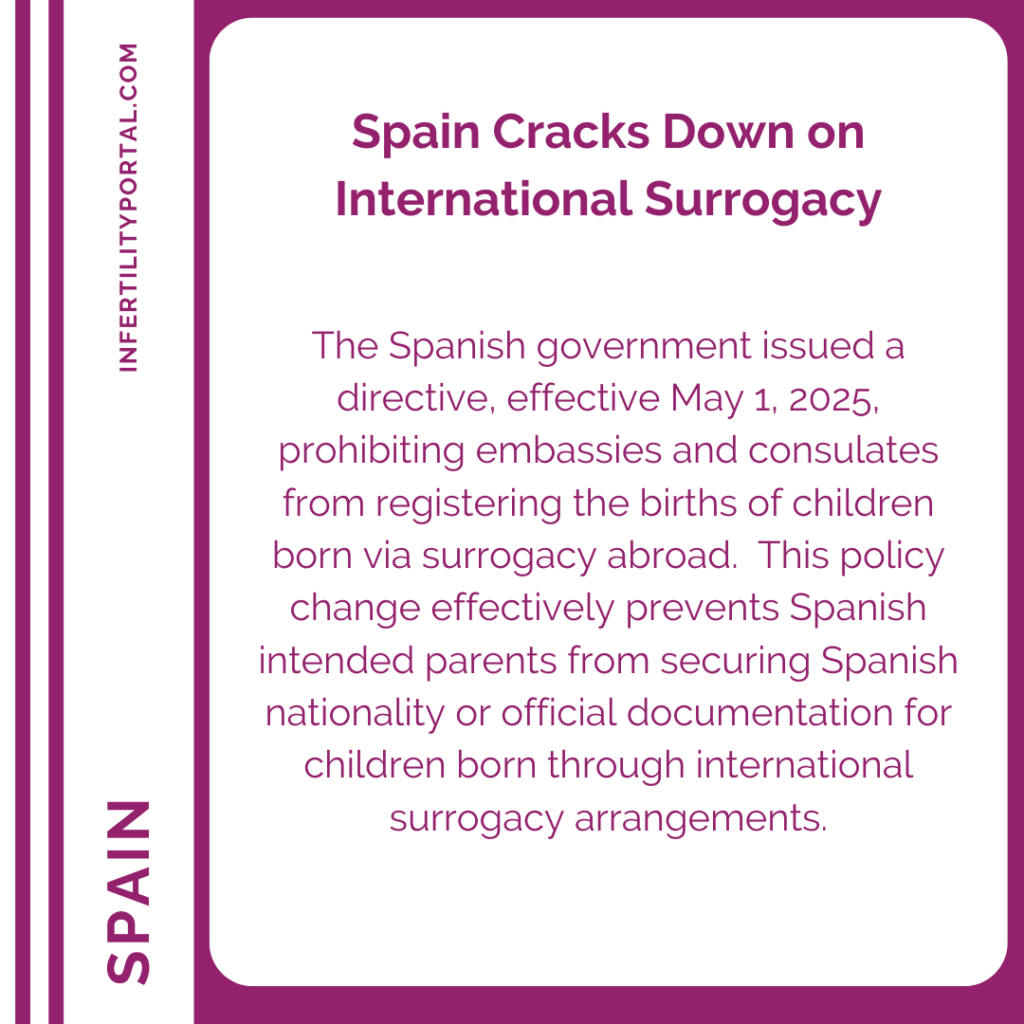

Spain has recently implemented stricter measures on international surrogacy, significantly impacting Spanish citizens seeking to become parents through surrogacy arrangements abroad.

New Policy Overview

Effective May 1, 2025, Spanish embassies and consulates are prohibited from registering children born via surrogacy in foreign countries. This policy change follows a 2024 ruling by Spain’s Supreme Court, which condemned surrogacy as an exploitation of women and a violation of children’s rights. Under the new regulations, diplomats cannot accept foreign documentation recognizing Spanish citizens as parents of children born through surrogacy.

Legal Background

Surrogacy has been prohibited in Spain since 2006. In the past, some Spanish families were able to register children born via surrogacy in other countries using foreign legal documents. This is no longer permitted. Now, Spain only recognizes a biological relationship for establishing parentage and requires formal adoption for any non-biological parent. These changes are intended to eliminate any perceived circumvention of Spanish surrogacy laws through foreign arrangements.

Biological Connection: One Parent vs. Both Parents

The new crackdown makes no exception for cases where the child is biologically related to one or both intended parents. However, the legal and administrative process may differ depending on the nature of the biological connection.

If the Child Is Biologically Related to Both Intended Parents

If both the intended mother and father are biologically related to the child, such as through the use of the mother’s egg and father’s sperm, with a gestational carrier abroad, Spain may recognize the biological father as the legal parent.

However:

The embassy will still not register the child at birth.

Both parents must return to Spain to pursue citizenship and registration through the Spanish courts.

The biological mother may face difficulties if she did not give birth to the child, as under Spanish law, the woman who gives birth is presumed to be the mother. This presumption must be legally rebutted.

If the Child Is Biologically Related to Only One Intended Parent

This is the more common situation, especially when donor eggs or sperm are used:

If the child is genetically related to the father, Spanish authorities may recognize his parentage after a legal process confirming biological paternity (e.g., DNA testing).

The non-biological parent—whether a partner or spouse—must undergo a formal adoption process in Spain after the child arrives.

No legal recognition will be granted to the non-biological parent without adoption, regardless of any foreign court decisions or documents.

In both scenarios, foreign birth certificates listing both intended parents will not be recognized by Spanish authorities. The pathway to legal recognition and citizenship must occur exclusively through Spanish domestic legal procedures.

Broader European Context

Spain’s actions mirror a wider trend across Europe, where countries like Italy and France are also moving to restrict or criminalize international surrogacy. These efforts reflect a shared concern over the ethical, legal, and human rights challenges associated with surrogacy arrangements that cross borders.

A Law That Favors Fathers, But Fails Mothers

Spain’s surrogacy restrictions do more than ban international arrangements. They expose a deeper legal bias. The law treats intended fathers and intended mothers unequally.

If a Spanish man is the biological father of a child born through surrogacy abroad, he can often be recognized as the legal parent. DNA testing and court procedures support this path, even though surrogacy is illegal in Spain.

But a Spanish woman, even if she is the biological mother, is not given the same rights. If she did not give birth, the law does not see her as a parent. Spanish law recognizes only the woman who gives birth as the legal mother.

This forces biological mothers to adopt their own children. The process can take months. During that time, they have no legal authority over the child. They must complete evaluations and paperwork, just to gain rights that fathers already have.

This system favors men based on biology but ignores women with the same connection. It reflects outdated views of motherhood and fails to keep up with modern reproductive science. The result is legal discrimination against women.

Spain’s surrogacy law is not only strict—it is unfair. It creates stress and legal uncertainty for families who use surrogacy. It gives legal standing to fathers while denying it to equally involved mothers.

Spain was once a leader in equality. It was among the first countries to legalize same-sex marriage and support LGBTQ+ families. That progress helped define its modern identity. But today, its surrogacy policies tell a different story. Spain now risks enforcing laws that protect men and marginalize women.