BRCA is a name derived from the abbreviation “Breast Cancer gene.” Breast Cancer gene 1 (BRCA) and Breast Cancer gene 2 (BRCA) have been found to influence a person’s chance of developing breast cancer. All men and women have two copies of breast cancer genes in their bodies – one from each parent. Breast cancer genes are tumor suppressor genes, producing proteins that help repair damaged genes in our cells, stopping them from becoming cancerous. Deleterious mutations in the breast cancer genes cause these genes not to function correctly, resulting in the gene failing to suppress the formation of tumors. People with breast cancer gene mutation are more likely to develop breast and ovarian cancer than the general population. Men and women with breast cancer gene variants also have an increased risk of prostate and pancreatic cancer, albeit a low risk.

In the general population, 1 in 8 women (12%) will develop breast cancer before 70 years.

- 55-65% of women with the Breast Cancer Gene 1 mutation will develop breast cancer before the age of 70 years, and 40-60% of these women will develop ovarian cancer before the age of 85 years.

- 20-45% of women with a Breast Cancer Gene 2 mutation will develop breast cancer before the age of 70, and 15-39% will develop ovarian cancer before the age of 85 years.

Therefore, women with the Breast Cancer Genes 1 or 2 mutation have a much higher risk of developing breast or ovarian cancer than those without the mutation. Men with Breast Cancer Gene mutations are at risk for various cancers, including breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and melanoma.

However, less is known about any link between breast cancer genes and their potential impact on fertility, and the studies on this link are uncertain:

- Lambertini’s study of 29 women diagnosed with breast cancer, who underwent egg freezing, found that BREAST CANCER GENES carriers demonstrated a consistent trend for lower AMH levels, and a lower number of eggs retrieved. In addition, those women who underwent ovarian tissue freezing had a lower number of eggs per fragment of tissue. However, the quality of the eggs appeared to be the same between Breast Cancer Gene carriers and none Breast Cancer Gene mutation carriers.

- Kwiatkowski et al.’s study (2015, Breast Cancer Gene Mutations Increase Fertility in Families at Hereditary Breast/Ovarian Cancer Risk, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127363) did a large study of 2,150 families and found that women carrying the Breast Cancer Gene mutation had a lower miscarriage rate, which they hypothesized suggested better egg quality. “Although Breast Cancer Gene mutations shorten the reproductive period due to cancer mortality, they compensate by improving fertility both in male and female carriers.”.

- Smith et al.’s study (https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2011.1697, Effects of Breast Cancer Gene 1 and Breast Cancer Gene 2 mutations on female fertility) examined 182 women diagnosed. It concluded that those who carried the BREAST CANCER GENES mutation genes had more children and shorter birth intervals than women without the mutation.

- Johnson et al.’s study (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert,2017.03.018,), Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels are lower in Breast Cancer Gene 2 mutation carriers, looked at 195 women and observed a significantly lower AMH level among Breast Cancer Gene 2 carriers compared with the control group. No difference in Anti-Müllerian hormone was observed for Breast Cancer Gene 1 carriers.

- Oktay et al.’s study of 177 women (DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2057 Journal of Clinical Oncology28, no. 2 (January 10, 2010) 240-244), they concluded that Breast Cancer Gene carriers were more likely to have a poor response to ovarian stimulation compared to Breast Cancer Gene -negative women.

- Procu et al.’s study (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-019-01658-9. Impact of Breast Cancer Gene 1 and Breast Cancer Gene 2 mutations on ovarian reserve and fertility preservation outcomes in young women with breast cancer) concluded that Breast Cancer Gene 1 patients had a higher risk of low ovarian reserve and a lower number of mature eggs suitable for freezing.

There appears to be no concise answer to whether there is a link between Breast Cancer Gene GENES mutation carriers and increased risk of infertility or premature ovarian aging. Breast Cancer Gene mutation women who are of childbearing age should consult a fertility specialist to assess their ovarian reserve with an Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH) measurement, antral follicle count (AFC), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and Estrogen (E2) levels. (Anti-Müllerian Hormone is a hormone secreted by the small ovarian follicles that are beginning to grow during that month’s cycle and is used to predict ovarian reserves). Even if the woman has not developed breast cancer, these tests should be undertaken. Anti-Müllerian Hormone levels go down to almost zero after chemotherapy. Although the Anti-Müllerian Hormone level will recover after a few months post-chemotherapy, the level of recovery is never the same as the level before chemotherapy. Therefore, these women should seriously consider preserving their fertility before initiating chemotherapy.

In addition, before chemotherapy, the woman should also seriously consider a consultation with a mental health professional, a fertility specialist, and their oncologist to discuss the options of:

- egg freezing,

- banking embryos,

- the option of ovary-sparing surgery – preserving the ovaries by moving the ovaries to a position outside of the radiation field,

- egg donation,

- surrogacy,

- adoption and child-free living.

Breast Cancer Gene mutations are hereditary, meaning the mutation was inherited from your parents. There is a 50% chance you will pass the Breast Cancer Gene mutation on to your children, which means there is no certainty an offspring will inherit the disease, and even if they do, there is no certainty that the affected person will develop cancer. In addition, effective treatment exists for various cancers, and science is making inroads into resolving or reducing the effect of multiple cancers. However, for some, there is tremendous anxiety involved in frequent preventative testing, and the 50% chance of passing this mutation on to a child who may develop breast or ovarian cancer is often overwhelming.

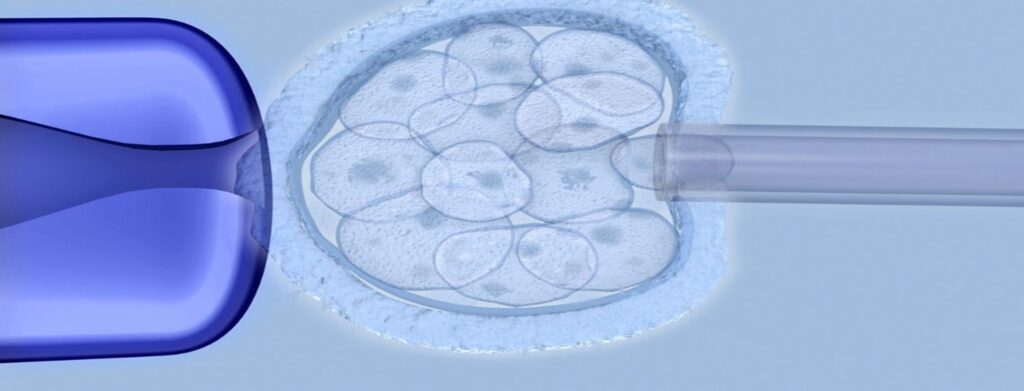

But what if you do not want to pass the Breast Cancer Gene mutation on to your children? An option is to freeze your eggs and create embryos later or create embryos and then perform Preimplantation Genetic Testing (PGT) on your embryos. Through PGT, embryos identified as non-carriers of the Breast Cancer Gene mutation can be implanted, ensuring that you will not transfer this gene to your children. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) and the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) both stated that performing preimplantation genetic testing on embryos to identify those that contain Breast Cancer Gene mutation genes is ethically justifiable.

Let us be clear; there is no conclusive evidence of a connection between Breast Cancer Gene mutations and an increased risk of infertility. If in doubt, book an appointment with an infertility specialist for an evaluation which should include an Anti-Müllerian Hormone test. However, cancer treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation impact women’s fertility. Therefore, if a person has been diagnosed with a positive test for one of the Breast Cancer Gene mutations, she has a higher chance of cancer and diminished fertility due to the cancer treatment. For all these reasons, a woman should consider preemptively preserving her fertility options.

Author: Karen Synesiou, Infertility Portal, Inc.